This blog is an ongoing assignment for Gov 1347: Election Analytics, a course at Harvard College taught by Professor Ryan Enos. It will be updated weekly and culminate in a predictive model of the 2024 presidential election.

Introduction – What are connections, if any between demographics and voter turnout? Can demographics and turnout be used to predict election outcomes? If so, how and how well?

As kids, our family, community, experiences, and upbringing all play a role in determining who we become as adults. The way we think, the choices we make, and even the things we care about are often rooted in childhood influences. Can the same be said about voting behavior? Wouldn’t it make sense that our demographics – age, race, income, education, etc – play roles in how we view political candidates?

For example, a person raised from a working-class background might prioritize economic policies regarding job security and unions. At the same time, someone from an affluent neighborhood may be more concerned about taxes. As the impact of these differences compounds over many years, they influence not only our voting behavior but also whether or not we even show up to vote in the first place.

The question is – how straightforward is this connection between demographics and voter turnout? What are the nuances within the numbers that we should pay attention to? As always, we’ll start with some data.

2016 – A Year of Particular Interest

While every election is. important, some stand out more than others due to social, economic, and political divides. 2016 was a sharp turning point for American politics as voters and candidates wrestled with questions about the gender gap, increased racial divide, shifting education, and more.

Therefore, let’s start with a logistic regression that predicts the likelihood of a voter casting a ballot for a Democrat or Republican based on factors including age, gender, race, etc:

##

## Call:

## glm(formula = pres_vote ~ ., family = "binomial", data = anes_train)

##

## Coefficients: (1 not defined because of singularities)

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 4.3583814 0.4366803 9.981 < 2e-16 ***

## age 0.0006984 0.0028117 0.248 0.80383

## gender -0.4294732 0.0934585 -4.595 4.32e-06 ***

## race -0.5482380 0.0605982 -9.047 < 2e-16 ***

## educ -0.3398141 0.0613322 -5.541 3.02e-08 ***

## income 0.0494349 0.0468039 1.056 0.29087

## religion -0.2148136 0.0421012 -5.102 3.36e-07 ***

## attend_church -0.2109916 0.0331518 -6.364 1.96e-10 ***

## southern -0.4096051 0.1051603 -3.895 9.82e-05 ***

## region NA NA NA NA

## work_status 0.0955178 0.0458378 2.084 0.03718 *

## homeowner -0.1765531 0.0822755 -2.146 0.03188 *

## married -0.0715981 0.0276917 -2.586 0.00972 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 2890.2 on 2087 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 2564.3 on 2076 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 2588.3

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4

Let’s dissect and interpret some of the important coefficients:

The large positive intercept of roughly 4.358 represents the baseline log-odds of voting Republican when all other variables are held constant.

The tiny age estimate of 0.0007 and p-value of 0.804 means that while the coefficient is positive, age has no meaningful impact on the likelihood of voting Republican based on the model. Historically, older voters tend to lean right, while younger generations seem to shift to the left, but the model seems to find this factor to be negligible.

The negative gender estimate of -0.429 and p-value of less than 0.001 suggests that women are less likely than men to vote Republican, which makes sense given historical trends in election data. Particularly for 2016 exit polls, the research found that women primarily favored Hillary Clinton, especially those of minority backgrounds.

The strong negative race estimate of -0.548 and p-value of 0.001 suggest that non-white voters are significantly less likely to vote Republican. This result is unsurprising as white voters have been historically more likely to vote Republican while Black, Hispanic, and other minority voters tend to lean left based on various social and economic policies. The results of the 2016 election confirmed this as Trump won the majority of white voters, but Clinton received overwhelming support from African American, Latino, and Asian voters.

In our lecture, we discussed how education can often be a significant predictor of voting behavior. In this model, we find that the coefficient is negative at -0.340, indicating that more educated individuals are less likely to vote Republican. In the context of 2016, many white college-educated women tended to lean Democratic, and as the divide continues to grow over time, the Democrats have continued to gain strength in this demographic subsection. In general, voters with greater education are exposed to more complex and nuanced discussions of political campaigns, making it harder for simplified and biased propaganda messages to penetrate voter behavior.

Surprisingly, the southern coefficient is negative and significant at -0.410, meaning that voters from the South are less likely to vote Republican according to this model. Historically, the South has remained a key stronghold for Republicans since the 1960s due to initiatives like the Southern Strategy, but changes in demographic shifts or other factors seem to be moving the needle in the other direction.

Overall, the difference between the null deviance and residual deviance shows that improvements were brought about by adding new predictors, meaning that it explains some of the variance in the data but there is still lots of room for improvement.

We can test this further by looking at in-sample accuracy:

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction Democrat Republican

## Democrat 746 336

## Republican 346 660

##

## Accuracy : 0.6734

## 95% CI : (0.6528, 0.6935)

## No Information Rate : 0.523

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : <2e-16

##

## Kappa : 0.3456

##

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 0.7304

##

## Sensitivity : 0.6832

## Specificity : 0.6627

## Pos Pred Value : 0.6895

## Neg Pred Value : 0.6561

## Prevalence : 0.5230

## Detection Rate : 0.3573

## Detection Prevalence : 0.5182

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.6729

##

## 'Positive' Class : Democrat

##

From the above, we find that the overall accuracy was roughly 0.6734 or 67.34%, presenting the proportion of total predictions (both Democrat and Republican) that were correct. Comparing it to the no Information Rate (NIR) of 52.3%, we can see that our model was significantly better than the NIR, as shown by the tiny p-value. Looking at the balanced accuracy (average of sensitivity and specificity) level of 0.6729, we see that it is similar to the overall accuracy, meaning that the model performs moderately well in both classes (Democrat and republican).

However, there is still lots of room for improvement, and considering accuracy alone can be misleading when thinking about sampling biases and imbalanced datasets. We may be looking at opportunities to increase our model complexity, such as random forests or gradient boosting to capture more non-linear interactions between demographics and voting behavior.

Before we do that, let’s take a look now at the out-of-sample accuracy:

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction Democrat Republican

## Democrat 184 80

## Republican 88 169

##

## Accuracy : 0.6775

## 95% CI : (0.6355, 0.7175)

## No Information Rate : 0.5221

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 4.301e-13

##

## Kappa : 0.3547

##

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 0.5892

##

## Sensitivity : 0.6765

## Specificity : 0.6787

## Pos Pred Value : 0.6970

## Neg Pred Value : 0.6576

## Prevalence : 0.5221

## Detection Rate : 0.3532

## Detection Prevalence : 0.5067

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.6776

##

## 'Positive' Class : Democrat

##

Compared to the previous in-sample accuracy, we see that the out-of-sample accuracy remains consistent, indicating that the model generalizes well to unseen data and isn’t overfitting to the training set. For example, if we had seen the in-sample accuracy be much higher than the above, that could suggest significant overfitting. Both moderate Kappa values of around 0.34-0.35 show that the model’s level of agreement with the actual outcomes is pretty consistent.

While there are certainly areas for improvement, altogether, this reveals signs of a robust model and demonstrates that the demographic variables included are fairly stable predictors of voting behavior across different samples of voters.

Don’t Miss the Forest for the Trees

As mentioned before, the logistic regression model is quite simple compared to the arsenal of other models at our disposal. One in particular that catches our attention is the random forest model, which can be used for both regression and classification tasks due to its versatility.

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction Democrat Republican

## Democrat 774 302

## Republican 318 694

##

## Accuracy : 0.7031

## 95% CI : (0.683, 0.7226)

## No Information Rate : 0.523

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : <2e-16

##

## Kappa : 0.4053

##

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 0.5469

##

## Sensitivity : 0.7088

## Specificity : 0.6968

## Pos Pred Value : 0.7193

## Neg Pred Value : 0.6858

## Prevalence : 0.5230

## Detection Rate : 0.3707

## Detection Prevalence : 0.5153

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.7028

##

## 'Positive' Class : Democrat

##

Immediately, we can see that strong accuracy of 0.703, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.683 to 0.7226, suggesting a fairly robust and confident estimate of the model’s performance. Compared to the No Information Rate (NIR), we see that our model performs significantly better than random guessing or simply predicting the majority class. Once again, the balanced accuracy here represents the average of sensitivity and specificity. With a value of 0.7028, we can see that it is able to better predict for both Democrats and Republicans compared to our previous logistic regression model.

Of course, we have some concerns about overfitting because these results are based on in-sample data. Let’s see how the model performs on unseen data and whether or not our results remain consistent:

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction Democrat Republican

## Democrat 187 70

## Republican 85 179

##

## Accuracy : 0.7025

## 95% CI : (0.6612, 0.7415)

## No Information Rate : 0.5221

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : <2e-16

##

## Kappa : 0.4053

##

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 0.2608

##

## Sensitivity : 0.6875

## Specificity : 0.7189

## Pos Pred Value : 0.7276

## Neg Pred Value : 0.6780

## Prevalence : 0.5221

## Detection Rate : 0.3589

## Detection Prevalence : 0.4933

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.7032

##

## 'Positive' Class : Democrat

##

Like before, we see that our out-of-sample accuracy is very close to the in-sample accuracy, showing that the model generalizes well to unseen data and isn’t drastically overfitting to maintain performance. Thus, we can say that the model seems to be inherently stronger than the logistic regression and better at capturing the complex interactions between education, race, religion, etc. This is particularly useful for a classification model in elections, whereby misclassifying voters from one party shouldn’t be systematically worse than for the other.

Simulation Testing

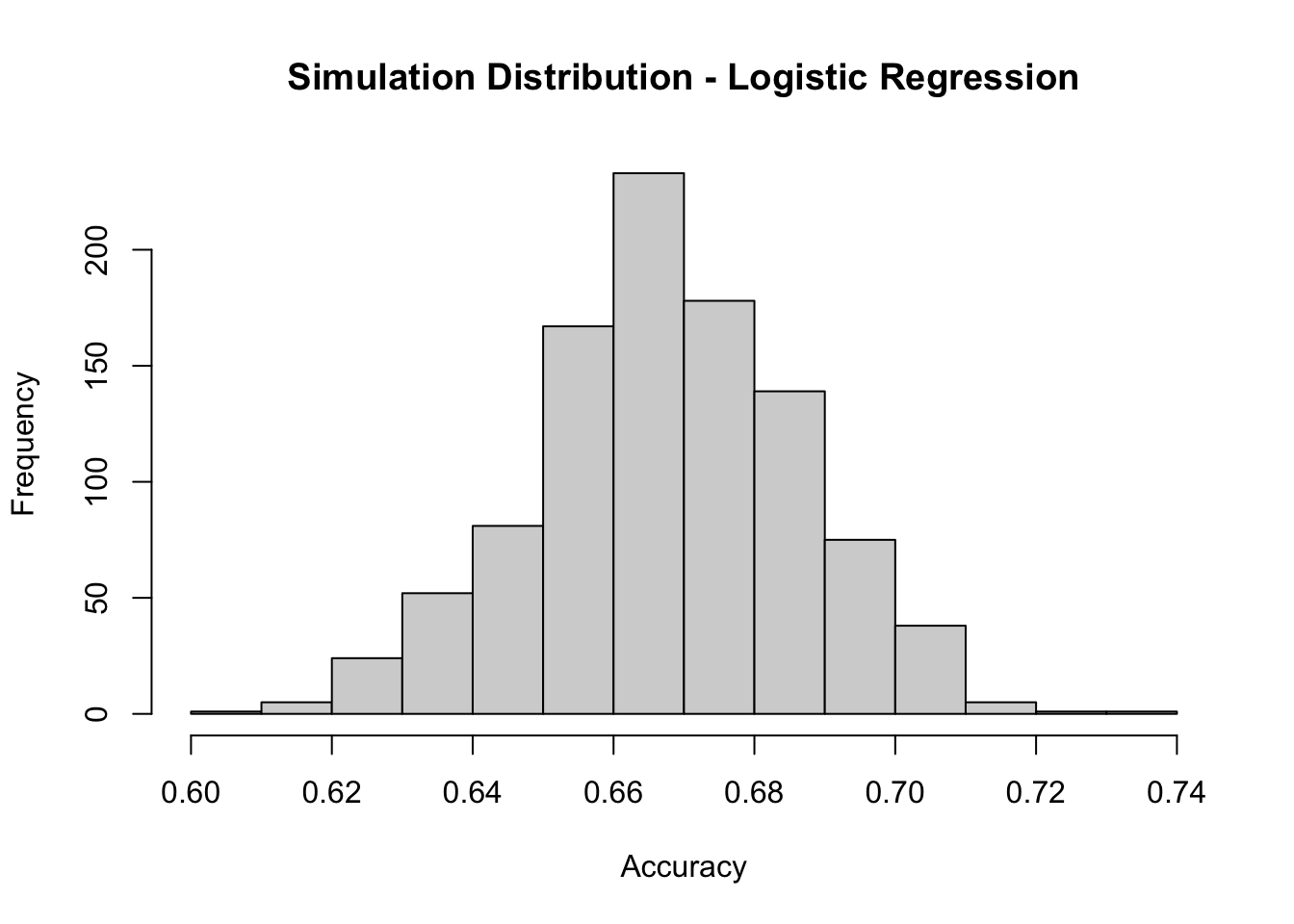

To understand more about our model performance, we’ll conduct a series of bootstrapped simulations on different randomly sampled splits of the dataset to examine the stability and variability of the models. Let’s take a look at the logistic regression model first:

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.6084 0.6564 0.6679 0.6678 0.6814 0.7351

From the histogram above, we see that the accuracy tends to hover around 66%, with relatively tight distribution results, indicating that the model is stable and performs consistently. This further adds confidence that it will generalize reasonably well when applied to new data, though there is room for improvement since the 66% accuracy still leaves quite some prediction error.

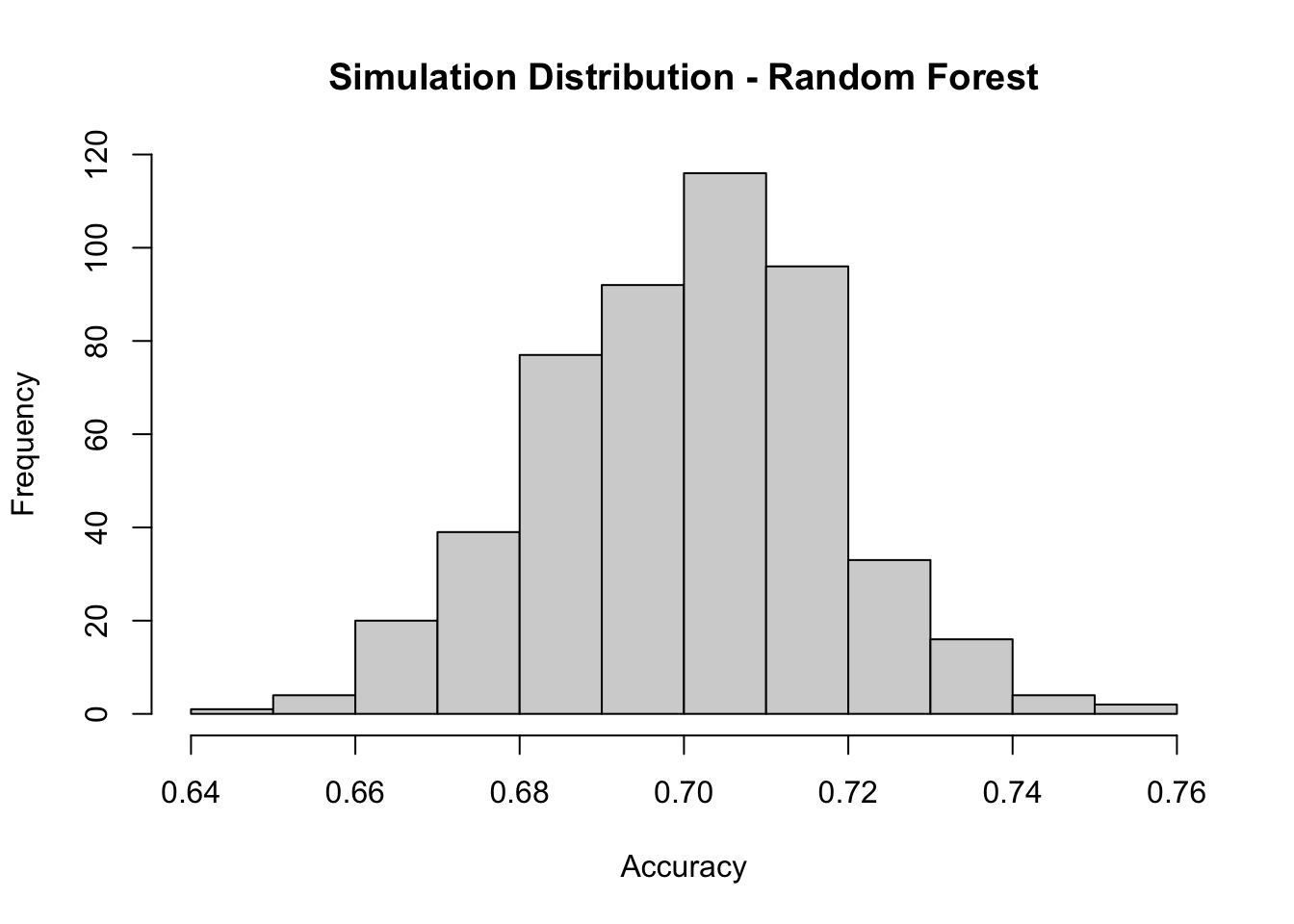

Now let’s repeat a similar test for the random forest model:

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.6488 0.6871 0.7006 0.7003 0.7121 0.7505

By running multiple simulations, we can assess whether the random forest model performs consistently or whether its accuracy fluctuates based on the data split. We see that the most frequent accuracy is around 0.70, with a moderate spread, meaning that there is some variability in the model’s accuracy depending on the specific dataset, but remains relatively stable.

Forests and Polling?

In terms of accuracy, the random forest model seems to capture the data most consistently across many of the different models we’ve explored so far. What if instead of adjusting our predictor variables, we adapted random forest to a new context – in this case, polling averages? In Blog Post 3, we had the opportunity to look into Elastic-Net and what its predictions are for the 2024 election.

The results yielded that Harris will win the vote share by a very slim margin:

## s1

## [1,] 51.79268

## [2,] 50.65879

Now, let’s see what random forest says based on the same training data:

## [1] 52.21456 48.67542

We can immediately see that the random forest model predicts a larger gap in vote share compared to the more linear elastic-net model. The ability of the random forest to capture complex interactions gives it an edge in terms of prediction and fit. In the context of polling, sudden shifts or specific weeks of high volatility might be more important for election outcome than what a more linear relationship might suggest.

Regardless, we see that the results predict a very tight race and reinforce the idea that even small events, such as last-minute campaign strategies, swapped candidates, or shifts in voter turnout could drastically affect outcomes.

Either way, our analysis here has provided greater context for what models to use and reveals valuable insights for how we can improve our models down the road…a road only 28 days long! Stay tuned for more!

Data Sources:

Data are from the GOV 1347 course materials. All files can be found here. All external sources are hyperlinked.